http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/7cff298e-f8b0-11e4-8e16-00144feab7de.html#ixzz3a1Vbhjvu

EM SQUARED

May 13, 2015 12:27 pm

EM currencies v Fed: India much better positioned than Brazil

Jonathan Wheatley/FT

Things have changed since the taper tantrum of 2013, for better and worse

As this week’s sell-off in Asian currencies reminds us, the mood among investors in emerging markets is one of nervous agitation. Behind it is an assumption that the US Federal Reserve will soon start raising interest rates, coupled with great uncertainty over just when this will happen.

If the Fed does raise rates as expected, which emerging market currencies will be most exposed? Kamakshya Trivedi and colleagues at Goldman Sachs have devised a scale of vulnerability that combines a country’s external balance, measured by its current account deficit or surplus, with its internal balance, measured by its rate of inflation.

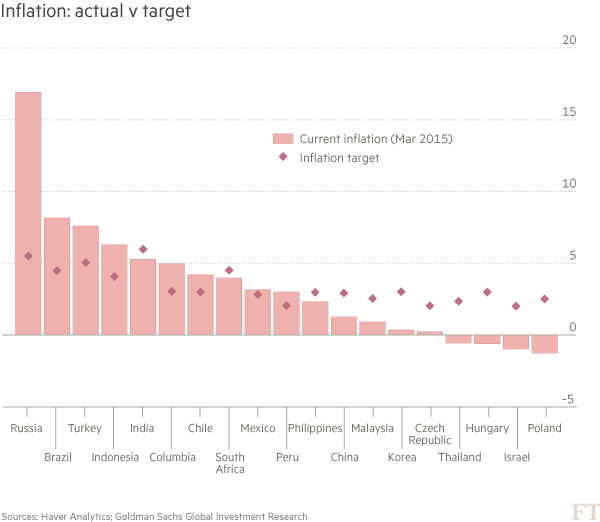

For the current account, they calculated a sustainable range and target level for each country’s deficit (or surplus) based on external debt stability, foreign asset/liability stability and a 20-year average, and compared this with the actual level. For inflation, they compared actual inflation with each country’s inflation target.

It was countries with such external and internal imbalances that led the “taper tantrum” sell-off two years ago, after the Fed said it would begin reducing its $85bn a month quantitative easing programme. But conditions have changed and the “fragile five” of Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey, which suffered most then, may no longer be the most exposed.

Indeed, as our first chart shows, India’s current account deficit is now smaller than what Goldman reckons is its sustainable level, while Indonesia’s is very close to its sustainable level. But Brazil, South Africa and Turkey are running deficits far beyond their sustainable levels.

As our second chart shows, Indian inflation at the end of March was inside the government’s target, as was South Africa’s. In contrast, inflation was running well above target in Brazil, Turkey and Indonesia.

By these measures, Brazil stands out as being much more vulnerable now than it was on the eve of the taper tantrum. Inflation has risen to more than 3 percentage points above target, and the current account deficit is almost 1 percentage point of GDP bigger than it was two years ago. India has worked hard to tackle both imbalances, with striking success — although its inflation target, at 6 per cent, is easier to hit than Brazil’s target of 4.5 per cent.

One thing that separates the two countries is that since the taper tantrum, India has had significant regime change — first with the appointment of Raghuram Rajan as central bank governor, then with the election of Narendra Modi as prime minister — whereas Brazil has not. True, Dilma Rousseff, Brazil’s president, having won re-election last year on a promise of no change to her statist and interventionist policies, has since given a market-friendly finance minister the job of dragging Brazil out of recession. But his job is daunting and he is doing it in the teeth of opposition from the president’s own ruling party.

What of other emerging markets? Combining its current account and inflation measures into one, Goldman produces the following diagram.

Trivedi and his colleagues stress that this is a snapshot of a moment in time. South African inflation, for example, had enjoyed the full benefit of lower oil prices at the end of March. Since then, inflation has begun to rise again, sending the country over towards the territory occupied in the chart by Brazil, Colombia and Turkey.

For these countries, Goldman argues, pressure for weaker currencies will persist, as depreciation would bring them closer to external balance. But this would also threaten to push inflation even higher. With its policy interest rate already at 13.25 per cent a year, Brazil cannot tighten monetary policy much further and is left with the struggle to achieve fiscal restraint. Turkey’s central bank would surely have raised interest rates were it not for intense political pressure against an ill-defined “interest rate lobby”.

A big current account deficit and high inflation are not the only imbalances. In South Korea, Hungary, Thailand and Israel, inflation has been below target for a long time. Scope for monetary easing is limited because interest rates are already very low, so policy makers may encourage currency weakness. Continued low interest rates will encourage credit expansion, fuelling further concerns.

And before you pick your winners and losers from the chart, remember it is a snapshot. Brazil’s currency has been recovering for much of the past two months, while India’s has been sliding. Signs of a change in sentiment? Or that one was oversold, the other overbought?

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2015.

Leave a Reply