Are markets too bearish on Brazil’s currency?

Mark Schaltuper, BMI Research | May 15 17:26 /FT

Brazil’s economy – as beyondbrics readers know – is in serious trouble, and the unorthodox policies of the country’s embattled president, Dilma Rousseff, have been major contributors to the Brazilian real’s sharp depreciation. But as an analyst who has a long-held negative view on the Brazilian real, it is interesting to ask – at this moment – whether we might be missing something now that investor sentiment has caught up with our bearish stance on the currency.

In short, given the real’s steep drop since 2011, has Brazil’s currency hit a bottom?

China’s economy is slowing and now there is the unpleasant reality that oil prices have collapsed and will likely not come back to the levels seen in the first half of 2014. This means that demand for Brazil’s steel exports will not return to the levels of recent years. Most economists are in agreement that Brazil’s economy will contract this year and the corruption scandal at state-owned oil company Petrobras, which we now know has lead to a $16.8bn impairment charge, only serves to deepen the perception that Brazilian assets are to be avoided at all costs.

This hardly bodes well for the exchange rate. Indeed, if you consider the notoriously poor business environment and the erosion of Brazil’s economic competitiveness following years of commodity exports, the latter of which has driven the exchange rate higher, enabled credit-fuelled consumption and inflated wages, the Brazilian real will have to drop a lot further against the US dollar to give non-commodity exporters a chance to play a bigger role in the economy.

Nevertheless, the night is always darkest before dawn and so I find myself wondering, what could pave the way for a reversal in the Brazilian real?

Below are a few factors that could make a bullish case for Brazil’s currency:

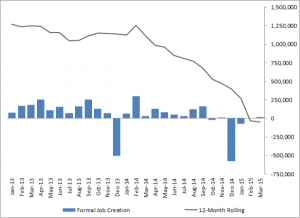

1) Job losses signal start of economic healing process

Years of disappointing fixed investment growth and arguably the most aggressive monetary tightening cycle in the world, which has seen the central bank hike its benchmark Selic target rate by 600bps to 13.25 per cent since April 2013, have not prevented unemployment from reaching historically low levels. The unemployment rate ended 2014 at 4.3 per cent – a record low – before jumping sharply to 6.2 per cent by March this year. While unemployment tends to rise in the early part of the year, something is definitely going on. For the first time since the global financial crisis, we are now seeing a larger number of jobs being destroyed than created on a 12-month rolling basis. This means that adverse economic conditions, abroad and domestically, are finally catching up with employers.

Total net formal government-registered job creation (non-seasonally adjusted)

What has changed? It is difficult to provide one answer, but it is probably a combination of factors ranging from lower oil prices and the corruption scandal causing job losses in the oil and gas sector, to a focus on fiscal consolidation by the new Rousseff administration after narrowly winning a second term last year. This is important, because it means that we are probably near the nadir of the economic slump. Moreover, rising unemployment and job losses mean that structurally high inflation will begin to come down.

2) Inflation is peaking

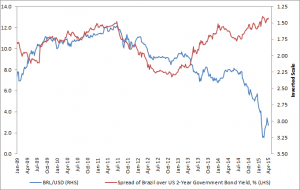

With the economic adjustment now in full swing and unemployment rising, previous efforts by the central bank to bring down inflation will at last prove fruitful. Consumer confidence is at its lowest level since 2001 and the government’s tighter fiscal policy under new finance minister Joaquim Levy means that unemployment benefits will be less generous. As such, demand-pull inflation, especially in the services sector, will begin to subside. This,. combined with fiscal tightening and high interest rates, means that inflation will peak in Q2 of this year and begin to head below the upper-band of the central bank’s very generous 2.5-6.5 per cent target range in 2016.

It is the loss of confidence in the ability of policy makers to control inflation that has seen a complete breakdown in the correlation between the exchange rate and Brazil’s interest rate differential with the US since 2013. A higher interest rate differential usually means higher returns for holding the higher-yielding currency (the carry trade). While we are still a long way away from seeing investors pile into real-denominated assets, falling inflation expectations will likely be positive for the Brazilian real.

3) Moving towards economic orthodoxy

Economic policy-making in Brazil has become the laughing stock of foreign investors. Nobody epitomised this better than former finance minister Guido Mantega, who not only continued a populist expansionary fiscal policy in the run-up to last year’s highly-contested general election but also made frequent comments about what central bank governor Alexandre Tombini should be doing. Little surprise then that no one took the central bank’s attempts to bring down inflation seriously.

However, by replacing Mantega with the axe-swinging Levy and recognising the need to introduce greater transparency and attract foreign investors in the wake of the Petrobras scandal, something may at last be changing. Don’t get me wrong, I am by no means saying that Rousseff has changed her ways and that Brazil is the next Mexico. My point is that things will unlikely get much worse from here on – at least as far as policy is concerned.

4) It’s a bargain!

The obstructiveness of Brazil’s business environment is well documented. The World Bank’s Doing Business 2015 report ranks Brazil 120th out of 189 countries, with the country doing particularly poorly in terms of ‘starting a business’ (167th) and ‘dealing with construction permits’ (174th). There is also the issue of ‘paying taxes’ in which Brazil ranks 177th out of 189 – it literally doesn’t get much worse. It will take you an average of 2,600 hours a year to pay your taxes in São Paulo versus an OECD average of 175.4.

Nevertheless, a sharp correction in asset prices and a string of bankruptcies relating to the Petrobras scandal, lower oil prices, and major exchange rate depreciation since 2011, mean that real-denominated assets are beginning to look enticing. Indeed, there have been reports that private equity firms are showing an increasing interest in real estate assets. Moreover, EM equity investors will likely be considering whether there is a bottom for several stocks listed on the Bovespa. We are keeping a close eye on Brazilian equities ourselves.

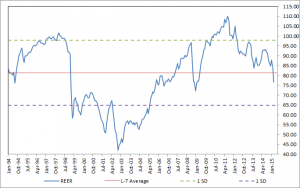

5) The real is less overvalued

Since the onset of the US dollar bull-run in mid-2011 and the start of the gradual sell-off in the Brazilian real, the unit has depreciated from a high of R$1.53 to the dollar, to R$2.98 today. In real effective exchange rate terms, the broad index has now fallen back below its long-term average of 81.36 to 76.61 in March, according to data from the Bank of International Settlements. From a technical perspective, too, a change in trend could be forming.

Brazil – real effective exchange rate, broad measure

And so, while it is difficult to turn outright bullish on the Brazilian real given the extremely weak economic fundamentals and an unlikely improvement in Brazil’s terms of trade any time soon, I wonder whether analysts and investors are currently too bearish.

Mark Schaltuper is head of Americas research at BMI Research.

Leave a comment