Majors’ Quandary: Why Drill for Oil When They Can Buy Somebody Else’s?

Rising oil-exploration costs and shrinking valuations of smaller players make takeovers likely

The rising costs of finding and producing oil were eating into profits even before global crude prices began to slide last summer from over $100 a barrel to about $66. PHOTO: REUTERS

By DANIEL GILBERT/WSJ

April 29, 2015 6:33 p.m. ET

The costs of finding oil are on the rise. The value of some smaller oil companies has tumbled. For the world’s biggest crude producers, this adds up to a question: Is it cheaper to buy someone else’s oil than to go digging for it?

As Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. report quarterly profits this week, executives are likely to face questions about their appetite for megadeals like the $70 billion takeover Royal Dutch Shell PLC disclosed earlier this month of BG Group PLC.

“There is no doubt that it’s much, much less expensive to take over a company than develop a new oil project in order to replace reserves,” says Leonardo Maugeri, a scholar at Harvard’s Belfer Center and a former executive of Italian oil company Eni SpA. He expects the most likely takeover candidates would be oil companies with a stock-market value between $10 billion and $40 billion—relatively small compared with Exxon’s $368 billion market capitalization.

The rising costs of finding and producing oil were eating into profits even before global crude prices began to slide last summer from over $100 a barrel to about $66 today. The price collapse has intensified a push by companies to cut costs and shed less-profitable operations.

BP PLC reported Tuesday its quarterly profit fell 40% from a year earlier, despite an increase in oil and gas output and a boost from its refining business. Analysts forecast profits for Exxon, Shell and Chevron will be at least 60% lower than a year ago.

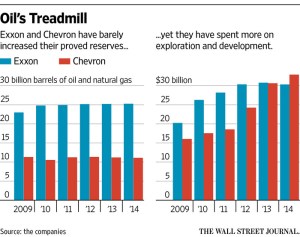

Since 2010, Exxon has spent an average of $29 billion a year on finding and tapping oil and gas, adding an average of 1.5 billion barrels a year to its proved reserves—the inventory of fuels it can pump at a profit. That works out to about $19 a barrel.

But it could get almost the same amount of fuel for less money by buying a smaller rival now that energy companies’ stock market values have fallen along with the price of crude.

For example, shale-oil driller Continental Resources Inc. has 1.35 billion barrels of proved reserves and a stock-market value of less than $20 billion—or less than $15 a barrel of proved reserves. The company, which is controlled by Chief Executive Harold Hamm, has lost about 22% of its stock-market value in the last 12 months. Continental declined to comment.

Some analysts think that some U.S.-focused midsize companies are likely to get even cheaper in coming months. Barclays analysts noted on Wednesday that the shares of some drillers appear to assume an oil price of $95 a barrel, far above today’s $58 price tag for U.S. crude—and more than futures contracts for oil a year from now.

Exxon and peers point out that they have found a lot of oil and gas that they haven’t yet booked as proved reserves, which they generally wait to do until committing the money to drill them. Exxon, for instance, says it has found the equivalent of 92 billion barrels of oil, of which a little more than a quarter is counted as reserves. It says it spent just $1.25 a barrel last year to find the oil and gas that it hasn’t yet committed to pump.

Tracking Crude’s Collapse

Because oil and gas wells decline over time, energy companies are constantly trying to replace them. The cost of finding more fuel has shot up for the world’s biggest energy companies, as they have pursued oil from beneath Kazakhstan’s icy Caspian Sea, developed facilities to export natural gas from the remote reaches of Western Australia and mined gunky crude from Canada’s oil sands.

Exxon declined to comment. But asked in March about potential acquisitions, Rex Tillerson, Exxon’s chief executive, told analysts that the oil-price crash offered “a whole lot of different kinds of opportunities, not just in terms of accessing new resources through various means but also getting the cost structure back to where we believe it is more appropriate.”

The biggest U.S. oil company wields tremendous takeover power with its ability to borrow cheaply and a hoard of shares that could be used in a merger.

For years, Exxon has saved money by reducing its global workforce, which is down by almost a third since its 1999 merger with Mobil Corp. Exxon now has fewer employees than 20 years ago and pumps 50% more oil and gas.

But getting bigger today might not create the savings energy companies are seeking, some analysts say. “They’ve got huge scale now,” says Tom Ellacott, a senior analyst at the consultancy Wood Mackenzie. “It has proved quite difficult to grow with that sort of scale. I think another wave of megamergers is quite unlikely at the moment.”

Instead, he says, companies will make deals to fill in gaps in their holdings or to building on existing strengths, as Shell proposes to do by swallowing BG.

Before the deal, Shell touted its ability to find oil and gas cheaply and played down the value of acquisitions. But then it paid a 50% premium for BG, enhancing its dominance as a global shipper of natural gas and getting potentially massive oil deposits off the coast of Brazil.

—Justin Scheck contributed to this article.

Write to Daniel Gilbert at daniel.gilbert@wsj.com

Leave a comment