http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/9daaa982-a9a0-11e5-843e-626928909745.html#ixzz3vpx8YoiQ

December 30, 2015 2:18 pm

Scandal-hit Petrobras faces new challenge

Joe Leahy in São Paulo/FT

Brazil’s largest oil group must grapple with large debts and lawsuits but can count on state backing

At a Christmas breakfast with journalists, Aldemir Bendine, the chief executive of Petrobras, said Brazil’s state-controlled oil company was aiming to become “smaller” thanks to an array of planned asset sales.

The comment was in marked contrast to the company’s ambitions a few years ago, when Petrobras was contracting a fleet of oil services vessels bigger than Britain’s Royal Navy in a race to exploit huge offshore discoveries near Rio de Janeiro, and thereby turn Brazil into an oil power.

But, for the most important company in Latin America’s biggest economy, simply surviving what has been an annus horribilis in 2015 ranks as an achievement for Petrobras, say analysts. Reeling from one of the world’s largest corruption scandals, the company in April published much-delayed results for 2014 in which it plunged to a net loss of R$21.6bn after a one-off hit of R$50.8bn (US$16.8bn) — of which R$6.2bn related to investigations into the company, with much of the remainder involving writedowns stemming from the oil price crash.

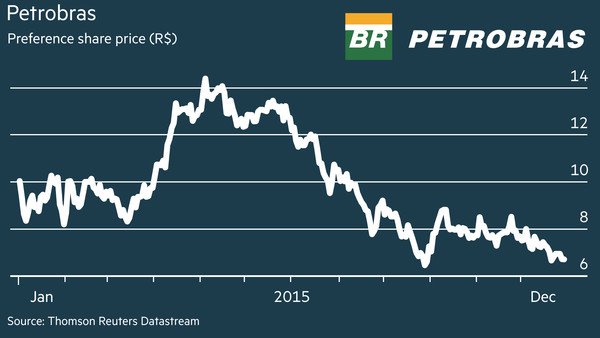

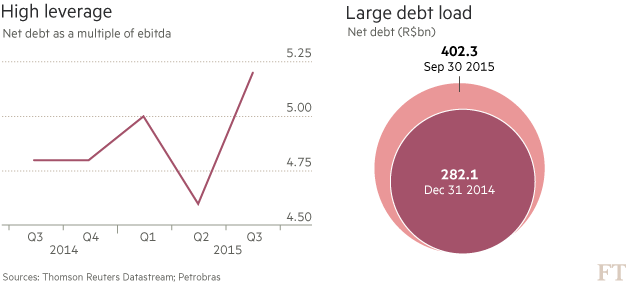

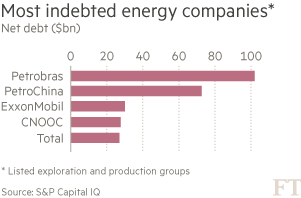

In November, Petrobras reported net income of R$2.1bn for the nine months to September 30, down 58 per cent compared to the same period last year. This partly reflected increased interest payments on the company’s towering borrowings — at $104bn, Petrobras has the largest net debt level in the energy sector. Petrobras’s preference shares have fallen almost 35 per cent over the past 12 months after the company stopped paying dividends.

2016 does not promise to be much easier for the company. Mr Bendine, who was appointed chief executive in February to clean up Petrobras, will need to fight investor lawsuits over losses incurred during the corruption scandal while increasing production and selling assets at a time whenoil is trading at multiyear lows.

Petrobras CEO Aldemir Bendine

Perhaps most challenging of all, Mr Bendine will have to reduce or at least manage Petrobras’s debt load. His success in doing so will be important not only for the company but for the rest of Brazil’s large universe of struggling corporate debtors and the solvencyof the country in general, with most analysts seeing the Brazilian state as the ultimate underwriter of Petrobras.

“Particularly with the oil and gas industry globally having the challenges that it is having, I think it is difficult to see how the company will meaningfully reduce leverage,” says Sarah Leshner, analyst at Barclays.

Few large oil companies globally have disappointed investor expectations in recent years as badly as Petrobras, say analysts. The company’s 2007 discoveries of “pre-salt” offshore oil reserves, so-called because they lie under a 2km-thick layer of the compound in ultra-deep waters off Brazil’s coast, kicked off a flurry of industry excitement.

Led by officials handpicked by Workers’ Party-led governments, Petrobras moved to exploit the discoveries by embarking on the largest corporate capital expenditure programme in the world. The company also began a huge refinery building project.

But things went awry in 2014 when police launched the “Lava Jato” — or Car Wash — investigation into allegations that former Petrobras directors collaborated with politicians and contractors to extract bribes from the company. Billions were allegedly looted from Petrobras and amid the turmoil the company was forced to postpone publication of its 2014 results, almost triggering technical default clauses on some debt covenants.

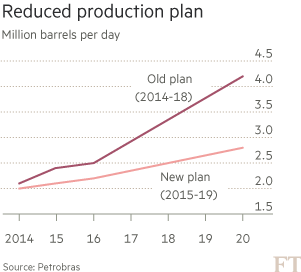

With its finances under pressure, Petrobras slashed investment plans, from $207bn for the period between 2014 and 2018, to $130bn for 2015 to 2019. Importantly, the company has cut its ambitious 2020 production target from 4.2m barrels of oil equivalent a day to 2.8m bpd, implying lower revenues in the years to come.

“Petrobras has seen its capital investment and production forecast negatively impacted by the Car Wash corruption scandal,” says Adrian Lara of GlobalData, a research firm.

Of most concern to investors is whether the company can continue to meet its debt repayments in spite of these constraints. Analysts estimate Petrobras has principal payments of $9bn to $12bn due each year for the next few years, so it will need to raise up to this amount annually from debt or equity markets.

Lucas Aristizabal of Fitch Ratings says Petrobras has the money to meet its near term obligations, given it has about $26bn of cash in hand. To maintain these healthy levels it is seeking to sell assets but, in spite of Mr Bendine’s hopes, this has proven difficult given low oil prices.

“Absent material divestitures, they will have to maintain access to the capital markets,” says Mr Aristizabal.

Petrobras showed in June that the markets remained open at the right price when it issued a $2.5bn, 100-year bond. It also enjoys the implicit support of Brazil`s state-controlled banks and has managed to secure funding from other channels, such as Chinese financial institutions, say analysts.

“The capital markets are never as closed as investors claim they are,” says Ms Leshner, predicting that while Petrobras would struggle to reduce leverage, it would meet its debt obligations.

Still, investors in Petrobras bonds are smarting, with the company leading a universe of Brazilian corporate debt that is trading at near distressed levels, say analysts.

The company is plagued by other uncertainties too. Apart from the Car Wash investigation, there is concern over infighting among Petrobras senior managers after chairman Murilo Ferreira suddenly resigned in November. Petrobras declined to comment for this article.

The company is also subject to government controls on the price at which it sells petrol to consumers.

But analysts say Petrobras has one big overriding factor in its favour — the backing of the state. As the near monopoly on fuel in one of the world’s biggest economies, Petrobras is Brazil’s version of “too big to fail”.

“Very few companies, almost no companies in the world, have that kind of market power,” says Mr Aristizabal.

| Antitrust watchdog opens new front in investigations |

|

Just when investors thought they had seen the full extent of the investigations into the Petrobras scandal, Brazil’s antitrust regulator last week opened a probe into the oil company’s business practices. The inquiry by Cade is into alleged cartel activity in the public bidding process for R$35bn of Petrobras contracts relating to refinery construction starting in 1998-99 and “gaining strength especially from 2003”, according to the regulator. The investigation names most of Brazil’s largest construction companies as alleged participants in the cartel but unlike investor lawsuits in the US against Petrobras, does not include the state-controlled oil group. Investor lawsuits in the US allege the Petrobras board was culpable for the scandal by ignoring warnings from independent directors and others about alleged wrongdoing at the company. Petrobras denies the allegations, saying it was a victim of wrongdoing, and is fighting the lawsuits. “There is robust evidence that the investigated companies and individuals would have entered [into] an agreement to fix prices, share the market and adjust conditions . . . in [the] public bids of . . . Petrobras,” said Cade. It added that the case was based on leniency agreements signed with two alleged members of the cartel and some of their employees. “Through the agreements, the signatory companies confessed their participation in the conduct and brought evidence of [a] cartel,” said Cade. The Cade case threatens to further paralyse Petrobras’s supply chain of builders and contractors at a time when the company is seeking to increase efficiency and reduce costs. |

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2015.

Leave a comment